Slide

doslider02

doslider01

Po drugiej stronie wymiaru

Auf der anderen Seite der Dimension

On the Other Side of the Dimension

Autor | artist: Jerzy Olek

Kurator | curator: Anna Panek-Kusz

miejsce | Ort | place: Galeriia OKNO, ul. 1 Maja 1, Słubice

Jerzego poznałam na studiach, około roku 2000. Był moim profesorem na ASP w Poznaniu. Miał już znaczny dorobek, wytyczał kierunki. Jak mówił Stefan Wojnecki, dał początek i rozwijał takie kierunki, jak fotografia analityczna, ekspansywna czy elementarna. Prowadzenie Galerii Foto-Medium-Art czy organizacja czterech Konferencji Wschód–Zachód „Europejska wymiana” pozostają świadectwem jego postawy i determinacji. Miał w sobie charyzmę, potrafił zarazić pasją. Nie tylko sam aktywnie działał jako artysta i kurator w kraju i za granicą, lecz też często dawał nam, studentom wkraczającym w świat sztuki, możliwość pierwszej prezentacji i uczestnictwa w akcjach artystycznych poza uczelnią. Ja z niej skorzystałam i tak rozpoczęła się nasza współpraca, jak chociażby poprzez organizację festiwalu lAbiRynT, który w 2010 r. przenieśliśmy do Słubic i Frankfurtu nad Odrą i do którego wkrótce jako współkuratorów zaprosił mnie oraz Michaela Kurzwelly’ego.

Okres tej współpracy ukształtował mnie jako artystkę, kuratorkę, stymulował do działań w ramach Galerii OKNO, prowadzenia warsztatów fotograficznych, Akademii lAbiRynT czy Grupy AKFA. Mogłam liczyć na radę i opinię Jerzego, zawsze bezkompromisowo szczerą. Dlaczego o tym piszę w kontekście jego wystawy indywidualnej? Dlatego że chciałabym go przedstawić nie tylko jako artystę, ale również jako nauczyciela i animatora. Wystarczy wspomnieć chociażby dialogi artystyczne w formie wystaw, spotkania i wspólne działania artystyczno-naukowe (np. z astrofizykiem Markiem Abramowiczem, kompozytorami Ryszardem Klisowskim, Rafałem Augustynem i Ryszardem Osadą, architektami Tadeuszem Sawą-Borysławskim iWitoldem Szymańskim, polonistą Kordianem Bakułą), czy organizowane od 1985 r. międzynarodowe warsztaty „Uczestnictwo we wspólnocie” w domu Jerzego w Starym Gierałtowie z udziałem artystów, poetów, filozofów.

Jerzy mawiał: „Artystą bywałem zazwyczaj wtedy, gdy chciałem skrótowo się wypowiedzieć – bez słów”. Ale i słów używał… ze szczególnym upodobaniem tworząc neologizmy. Takie dążenie do przekraczania granic zaznaczyło się też w twórczości wizualnej i teoretycznej. Inspirował, choć też potrafił dezorientować tych, którzy podążają utartymi ścieżkami. Znosił granice między dyscyplinami, poszerzając ich wymiary poprzez bezwymiary, iluzje, aluzje, dekonstrukcje…

Często stosował artystyczny recykling. Stare płyty CD stanowiły bazę pod rysunki (Druga strona, 2016), podobnie jak tekturowe oprawy studenckich prac zaliczeniowych, które ciął na mniejsze formaty. Stare kasety po Polaroidach przydały się jako ramki do setek prac. Szczególnie jednak wspominam nasz wspólny projekt Ukryta przestrzeń (2012): trzysta miniaturowych fotografii, oprawionych w ramki po slajdach, zostało umieszczonych na drewnianym szkielecie mojego domu w Uradzie; widz musiał ich szukać, poruszając się po labiryncie placu budowy. Zamontowane wtedy miniatury wciąż znajdują się na swoim miejscu, niczym kamienie węgielne, przykryte tynkiem z gliny. Jedna z prac nie została zakryta i do dziś można ją zobaczyć.

Obecna wystawa prac Jerzego prezentowana w ramach Festiwalu Nowej Sztuki lAbiRynT prawie rok po śmierci artysty i mojego przyjaciela nie przedstawi jego sylwetki w sposób wyczerpujący. Nie odpowie na wszystkie „dlaczego”, bo i on sam borykał się z tym pytaniem: „Dlaczego ciągle zadaje sobie pytanie «dlaczego»? Dlaczego stale rozbijam przestrzeń, aby ją scalać? (…) Dlaczego własne odsłanianie służy mi do skrywania siebie?”.

***

A jednak nie opuszcza mnie niepokój związany z niepewnością tak sensu mojego działania, jak i jego rezultatu. Mówiąc w dużym uproszczeniu, idzie mi o nieprzekładalność na język wizualny intuicji związanych z wielopostaciowością przestrzeni, tych niemożliwych, a mimo to – jak przypuszczam – spełniających się w innych wymiarach.

Jerzy Olek

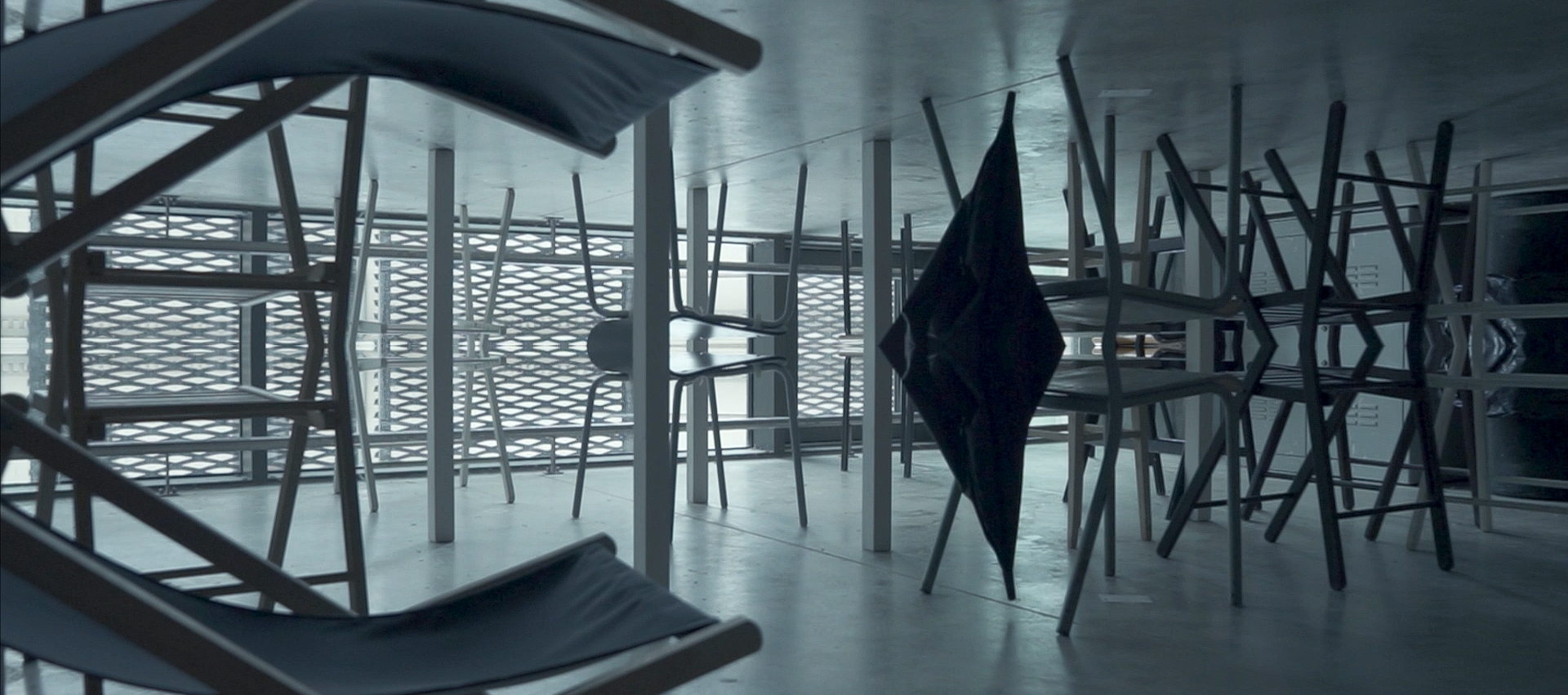

W swoich twórczych poszukiwaniach Jerzy Olek wyszedł od fotografii, ale w miarę upływu czasu coraz mniej czuł się fotografem, a bardziej artystą w sensie ogólnym. Jego wystawy, zawsze precyzyjnie planowane do przestrzeni, często nietypowej, same stawały się rozbudowanymi instalacjami. Tak było np. w wypadku wystawy na murach zamku w Wojnowicach (Bezwymiar iluzji, 2002), na drewnianej konstrukcji domu w Uradzie (Przestrzeń ukryta, 2012), w kościele Mariackim we Frankfurcie nad Odrą (Przedłuż myślą napotkaną linię, 2013), ale też w miejscach bardziej typowych, jak w Muzeum Miejskim Arsenał we Wrocławiu (Mapy rozmaitości, 2004) czy galerii Okno w Słubicach (Głębia płaskiego, 2003).

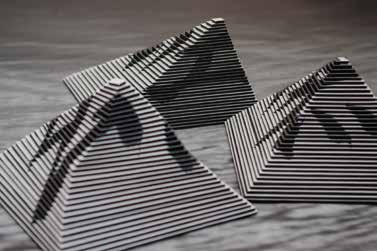

Nierzadko fotografia stawała się punktem wyjścia do nowej formy. Artysta ciął fotografie, rysował po nich, tworzył z nich kolaże i obiekty, uprzestrzenniając je poprzez nawarstwianie – jak wpiramidkach wykonanych z wielu naklejonych na siebie coraz mniejszych fragmentów wycinanych z kolejnych kopii tego samego zdjęcia (Zaginanie przestrzeni, 2007; Kształt ideogramu, 2010, Kult krawędzi, 2005). Nie wystarczało mu budowanie iluzji przestrzeni w samej fotografii – poprzez swoje obiekty wyprowadził fotografię z dwóch wymiarów w trójwymiar. Tak powstała np. Przestrzeń zakłócona (2011), w której iluzja istnieje na kilku poziomach. Zdjęcie iluzjonistycznego muralu na nowej kamienicy we Frankfurcie nad Odrą przedstawiającej historyczny budynek stojący w tym miejscu przed wojną zostało poddane procesowi zakłócania i uprzestrzenniania – można by powiedzieć, że było to odbudowanie kamienicy w trójwymiarze.

Ale i trójwymiar nie wystarczał, Jerzego kusiły wyższe wymiary. Swoje intuicje w tym względzie wyrażał m.in. poprzez zagęszczanie obrazu. Sztandarowym przykładem jest tu Kolczatka (2008). Wychodząc od stoosiemdziesięciościanu gwiaździstego zbudowanego z kartonu (dokumentuje to Kolczatka pusta), oklejał go trójkątami wyciętymi ze zdjęć tegoż obiektu, ponownie fotografował oklejone fragmenty, powtarzał proces kilka razy… aż sama Kolczatka stała się obiektem kryjącym w sobie obrazy obrazów w obrazie, perspektyw wielu inych perspektyw. Ale i Kolczatka pełna (jak ją nazwał) była tylko krokiem dalszym do nowych obiektów, inaczej tworzących przestrzenie w przestrzeni (Zagięta przestrzeń, 2012).

Zainteresowanie przestrzenią szło wparze z pasją do ujawniania mechanizmównaszego widzenia. Budowa oka, działanie umysłu i wyuczone konwencje odczytywanie obrazu sprawiają, że tak podatni jesteśmy na iluzje wzrokowe. A to następny wielki temat, który można wyczytać w pracach artysty.

W iluzyjność rzeczywistości Jerzy wszedł przez linię. Jedna z wczesnych prac zestawia narysowaną ołówkiem linę i jej powiększenie metodą fotograficzną (Powiększenie linii, 1982). Później uzupełnił ją jeszcze obrazem z mikroskopu skaningowego, kompletnie odrealniającego coś, co były zwykłą kreską na papierze. A linia istotna była dla niego zarówno w swojej fizyczności, jak i jako idea. Pojawia się w postaci taśm naklejanych na ścianę i budujących rzuty figur, w aranżacji ekspozycji (np. Głębia płaskiego), jako pasy fotografii naklejanych na długie listwy lub wolno wiszące (z sześcianem, z motywami japońskimi, inspirowane anaglifami, z zapisem spotkań ze Zbigniewem Dłubakiem, Tadeuszem Różewiczem czy Stanisławem Lemem). Nie zapominajmy o linii w rysunkach, np. w serii Figura możliwa (2007), w dużym stopniu zmierzającej ku… figurze niemożliwej. Warto przypomnieć też wydarzenie z 2013 r., kiedy podczas festiwalu lAbiRynT, w rocznicę swoich 70. urodzin, w kościele Mariackim we Frankfurcie nad Odrą Jerzy zrealizował instalację pt. Przedłuż myślą napotkaną linię składającą się z pasków białej płyty piankowej z narysowaną na niej różnie pofalowaną linią. Paski te porozkładał na posadzce gotyckiego kościoła i oświetlił świecami. Widzowie lawirowali między rozłożonymi liniami i kontemplowali je przy muzyce fletu.

Kontynuując fascynację linią, w roku 1996 Jerzy stworzył cykl fotograficzny Linie światła, aw2013 r. wspólnie zgrupą artystów zrealizował projekt Weneckie linie oraz na Biennale wWenecji przeprowadził akcję pt. Zmierz Biennale. Akcja ta, będąca hołdem złożonym Dumchampowi w 100. rocznicę jego Trzech standardowych zatrzymań, polegała na tym, że odwiedzający mieli linkami o długości 101 cm zmierzyć według własnego pomysłu wenecką imprezę. Jerzy dokonywał również analizy pojmowania linii, zapraszając do zaprezentowania swojej definicji 59 osób: artystów, fizyków, filologów, kompozytorów, matematyków, poetów. Całość została zebra w książeczce O linii (2013).

Zainteresowanie właściwościami medium prowadziło artystę ku przyglądaniu się materialnym nośnikom obrazu fotograficznego. Papier, emulsja, wywoływacz i utrwalacz – plus światło i czas. Tym właśnie jest fotografia. Dlatego nie dziwi seria chemigrafii polegających na malowaniem chemią fotograficzną po papierze światłoczułym (Splot przypadków, 2004), bez użycia aparatu czy filmu. Z tego powodu też pojawił się tryptyk Pochłaniacz fantomów (2015): Naświetlanie – złożony z kartek niewywołanego, a więc cały czas naświetlającego się papieru fotograficznego; Wywołanie – z kartek wywołanego papieru, oraz Negatywowanie – z rzędów negatywów.

Jeszcze jednym istotnym aspektem twórczości Jerzego Olka jest idea pustki. Zaczęło się od podróży do Japonii, gdzie zaraził się ideami filozofii zen. Już w pierwszej połowie lat 80. zrealizował projekt Puste–pełne będący wyrazem przekonania, że to, co najwięcej mówi, jest często małe i nienarzucające się, a dojść do niego można poprzez kontemplację. W Japonii zrobił serię prac Pusta obecność (1981), zaznaczając swoją obecność kwadracikiem białego papieru. Tam, w ogrodzie kamiennym przy świątyni Kodai-ji, powstała zapraszająca do medytacji instalacja 5 spojrzeń na stożek: dzień, noc (2012). Stamtąd wreszcie Jerzy przywiózł namalowane na jego życzenie przez japońskiego artystę Yasu Suzukę ideogramy znakomicie podsumowujące jego zainteresowania artystyczne: iluzja, pustka, przestrzeń.

Anna Panek-Kusz

Ich lernte Jerzy um das Jahr 2000 herum kennen, als ich studierte und er mein Professor an der Kunstakademie in Poznań war.

Er hatte bereits ein beachtliches Werk geschaffen, er war richtungsweisend. Wie Stefan Wojnecki sagte, hat er Trends wie die analytisch-expansive oder die elementare Fotografie hervorgebracht und entwickelt. Das Betreiben der Foto-Medium-Art Galerie oder die Organisation der vier Ost-West-Konferenzen „Europäischer Austausch“ zeugen von seiner Haltung und Entschlossenheit. Er hatte Charisma und konnte uns mit seiner Leidenschaft anstecken. Er war nicht nur selbst als Künstler und Kurator im In- und Ausland tätig, sondern gab uns Studenten, die in die Welt der Kunst eintraten, oft die Möglichkeit, ihre erste Präsentation zu machen und an künstlerischen Aktionen außerhalb der Universität teilzunehmen. Das habe ich genutzt, und so begann unsere Zusammenarbeit, etwa bei der Organisation des lAbiRynTFestivals, das wir 2010 nach Słubice und Frankfurt/Oder brachten und zu dem er mich und Michael Kurzwelly bald als KoKuratoren einlud.

Die Zeit dieser Zusammenarbeit hat mich als Künstlerin und Kuratorin geprägt und mich dazu angeregt, in der OKNO-Galerie zu arbeiten, Fotografieworkshops zu leiten, die lAbiRynT-Akademie oder die AKFA-Gruppe zu gründen. Ich konnte mich auf Jerzys Rat und seine Meinung verlassen, die immer kompromisslos ehrlich war. Warum schreibe ich darüber im Zusammenhang mit seiner Einzelausstellung? Weil ich ihn nicht nur als Künstler, sondern auch als Lehrer und Animator vorstellen möchte. Erwähnt seien nur die künstlerischen Dialoge in Form von Ausstellungen, Begegnungen und gemeinsamen künstlerischwissenschaftlichen Aktivitäten (z. B. mit dem Astrophysiker Marek Abramowicz, den Komponisten Ryszard Klisowski, Rafał Augustyn und Ryszard Osada, den Architekten Tadeusz Sawa-Borysławski und Witold Szymański, dem polnischen Sprachlehrer Kordian Bakuła) oder der internationale Workshop „Partizipation in der Gemeinschaft“, der seit 1985 in Jerzys Haus in Stare Gierałtów unter Beteiligung von Künstlern, Dichtern und Philosophen organisiert wurde.

Jerzy pflegte zu sagen: „Ich war meist Künstler, wenn ich mich kurz ausdrücken wollte – ohne Worte“. Aber er benutzte auch Worte… mit einer besonderen Vorliebe für die Schaffung von Neologismen. Dieser Wunsch, Grenzen zu überschreiten, zeigte sich auch in seinem visuellen und theoretischen Werk. Er inspirierte, aber er verstand es auch, diejenigen zu verwirren, die die üblichen Wege gingen. Er löste die Grenzen zwischen den Disziplinen auf, erweiterte ihre Dimensionen durch Dimensionslosigkeit, Illusionen, Anspielungen, Dekonstruktionen…

Oft nutzte er künstlerisches Recycling. Alte CDs dienten als Grundlage für Zeichnungen (Die andere Seite, 2016), ebenso wie die Pappeinbände von Studienarbeiten, die er in kleinere Formate schnitt. Alte Polaroid-Kassetten dienten als Rahmen für Hunderte von Werken. Besonders in Erinnerung geblieben ist mir aber unser gemeinsames Projekt Der Verborgene Raum (2012): Dreihundert Miniaturfotografien, gerahmt in Diarahmen, wurden auf der Holzkonstruktion meines Hauses in Urad platziert; der Betrachter musste sie suchen, indem er sich durch das Labyrinth der Baustelle bewegte. Die damals montierten Miniaturen sind noch an ihrem Platz, wie Ecksteine, mit Lehmputz bedeckt. Eines der Werke wurde nicht abgedeckt und kann heute noch besichtigt werden.

Die aktuelle Ausstellung von Jerzys Werk, die im Rahmen des Festivals Neuer Kunst lAbiRynT fast ein Jahr nach dem Tod des Künstlers und meines Freundes gezeigt wird, kann sein Profil nicht erschöpfend darstellen. Sie wird nicht alle „Warum“- Fragen beantworten, denn auch er selbst hat mit dieser Frage gerungen: „Warum frage ich mich ständig nach dem ‚Warum‘? Warum breche ich ständig den Raum auf, um ihn zu verschmelzen? (…) Warum dient meine eigene Enthüllung dazu, mich zu verbergen?“.

***

Und doch gibt es eine Unruhe über die Ungewissheit sowohl der Bedeutung meines Tuns als auch seines Ergebnisses. Vereinfacht gesagt, geht es mir um die Unübersetzbarkeit von Intuitionen in die visuelle Sprache, die mit der Vielgestaltigkeit des Raums zusammenhängen, die unmöglich sind und sich doch – so vermute ich – in anderen Dimensionen erfüllen.

Jerzy Olek

Jerzy Olek begann seine kreativen Erkundungen mit der Fotografie, aber mit der Zeit fühlte er sich immer weniger als Fotograf und immer mehr als Künstler im allgemeinen Sinne. Seine Ausstellungen, die immer für einen bestimmten, oft untypischen Raum geplant wurden, entwickelten sich zu eigenständigen Installationen. Dies war beispielsweise der Fall in seiner Ausstellung an den Wänden des Schlosses in Wojnowice (Die Dimensionslosigkeit der Illusion, 2002), an der Holzkonstruktion meines Hauses in Urad (Der verborgene Raum, 2012), in der Marienkirche in Frankfurt (Oder) (Verlängere in Gedanken die vorgefundene Linie, 2013), aber auch an typischeren Orten wie der städtischen Kunsthalle Arsenał in Wrocław (Karten der Diversität, 2004) oder der Galerie Okno in Słubice (Die Tiefe des Flachen, 2003).

Nicht selten wurde eine Fotografie zum Ausgangspunkt für eine neue Form. Der Künstler zerschnitt Fotografien, zeichnete darauf, schuf daraus Collagen und Objekte und verräumlichte sie, indem er sie schichtete – wie in Pyramiden aus vielen übereinander geklebten Teilen derselben Fotografie, aus immer kleineren Fragmenten, die er aus aufeinanderfolgenden Kopien derselben Fotografie herausschnitt (Die Verbiegung des Raumes, 2007; Die Form des Ideogramms, 2010, Der Kult des Randes, 2005). Es genügte ihm nicht, die Illusion des Raums in der Fotografie selbst aufzubauen – durch seine Objekte brachte er die Fotografie aus der Zweidimensionalität in die Dreidimensionalität. So schuf er zum Beispiel Gestörter Raum (2011), in dem die Illusion auf mehreren Ebenen existiert. Die Fotografie einer illusionistischen Wandmalerei auf einem neuen Mietshaus in Frankfurt (Oder), die ein historisches Gebäude zeigt, das dort vor dem Krieg stand, wurde einem Prozess der Störung und Verräumlichung unterzogen – man könnte sagen, es war eine Rekonstruktion des Mietshauses in drei Dimensionen.

Aber selbst die Dreidimensionalität reichte nicht aus; Jerzy war von höheren Dimensionen angetan. Er drückte seine diesbezüglichen Intuitionen unter anderem durch eine Verdickung des Bildes aus. Das Paradebeispiel dafür ist Stachelkugel (2008). Ausgehend von einem einhundertsechsundachtzigdimensionalen stellaren Ikosaeder aus Pappe (dokumentiert in Die leere Stachelkugel), bedeckte er es mit Dreiecken, die er aus Fotografien desselben Objekts ausgeschnitten hatte, fotografierte die bedeckten Fragmente erneut und wiederholte den Vorgang mehrere Male… bis der Stachel selbst zu einem Objekt wurde, das Bilder von Bildern in Bildern, Perspektiven aus vielen anderen Perspektiven versteckt. Aber auch Die volle Stachelkugel (wie er es nannte) war nur ein weiterer Schritt hin zu neuen Objekten, die Räume im Raum anders gestalten (Die Verbiegung des Raumes, 2012).

Dieses Interesse am Raum ging Hand in Hand mit einer Leidenschaft für die Entdeckung der Mechanismen unseres Sehens. Die Struktur des Auges, die Funktionsweise des Geistes und die erlernten Konventionen beim Lesen eines Bildes machen uns so anfällig für visuelle Täuschungen. Und das ist ein weiteres großes Thema, das sich im Werk des Künstlers wiederfindet.

Jerzy hat sich mit der Illusion der Realität durch die Linie auseinandergesetzt. In einem seiner frühen Werke stellt er eine mit Bleistift gezeichnete Linie einer fotografischen Vergrößerung gegenüber (Linienvergrößerung, 1982). Später ergänzte er sie mit dem Bild durch ein Rastermikroskop, wodurch etwas, das eine einfache Linie auf dem Papier war, völlig unwirklich wurde. Und die Linie war für ihn sowohl in ihrer Körperlichkeit als auch als Idee wichtig. Sie erscheint in Form von Klebebändern, die an die Wand geklebt werden und Projektionen von Figuren bilden, in der Gestaltung von Ausstellungen (z. B. Die Tiefe des Flachen), als Fotostreifen, die auf lange Latten geklebt werden, oder frei hängend (mit einem Würfel, mit japanischen Motiven, inspiriert von Anaglyphen, mit Aufzeichnungen von Treffen mit Zbigniew Dłubak, Tadeusz Różewicz oder Stanisław Lem). Nicht zu vergessen ist die Linie in den Zeichnungen, zum Beispiel in der Serie Mögliche Figur (2007), die weitgehend auf… die unmögliche Figur abzielt. Es lohnt sich auch, an ein Ereignis aus dem Jahr 2013 zu erinnern, als Jerzy während des lAbiRynTFestivals anlässlich seines 70. Geburtstags in der Marienkirche in Frankfurt (Oder) eine Installation mit dem Titel Verlängere in Gedanken die vorgefundene Linie realisierte, die aus Streifen weißer Schaumstoffplatten bestand, auf die eine unterschiedlich gewellte Linie gezeichnet war. Er breitete diese Streifen auf dem Boden der gotischen Kirche aus und beleuchtete sie mit Kerzen. Die Zuschauer bewegten sich zwischen den ausgebreiteten Linien hin und her und betrachteten sie zur Musik einer Flöte.

Seine Faszination für die Linie setzte Jerzy 1996 mit der Fotoserie Lichtlinien fort. 2013 realisierte er zusammen mit einer Gruppe von Künstlern das Projekt Linien Venedigs und führte auf der Biennale von Venedig eine Aktion mit dem Titel Vermesse die Biennale durch. Diese Aktion, eine Hommage an Dumchamp zum 100. Jahrestag seiner 3 stoppages étalon, bestand darin, dass die Besucher aufgefordert wurden, das venezianische Ereignis nach ihren eigenen Vorstellungen mit 101 cm langen Schnüren zu messen. Jerzy analysierte auch das Verständnis der Linie und lud 59 Personen ein, ihre Definition zu präsentieren: Künstler, Physiker, Philologen, Komponisten, Mathematiker, Dichter. Das Ganze wurde in der Broschüre

Über die Linie (2013) zusammengefasst.

Sein Interesse an den Eigenschaften des Mediums führte den Künstler dazu, sich auch mit dem

materiellen Medium des fotografischen Bildes zu

beschäftigen. Papier, Emulsion, Entwickler und

Fixierer – sowie Licht und Zeit. Das ist es, was

Fotografie ausmacht. Daher ist es nicht verwunderlich, eine Serie von Chemigrafien zu sehen, bei

der mit Fotochemie auf lichtempfindlichem Papier gemalt wird (Zufallsgeflecht, 2004), ohne dass

eine Kamera oder ein Film verwendet wird. Dies

ist auch der Grund für das Triptychon Phantomfänger (2015): Belichtung – bestehend aus Blättern von unentwickeltem und daher immer belichtetem Fotopapier; Entwicklung – bestehend

aus Blättern von entwickeltem Papier, und Negierung – bestehend aus Reihen von Negativen.

Ein weiterer wichtiger Aspekt im Werk von Jerzy

Olek ist die Idee der Leere. Es begann mit einer

Reise nach Japan, wo er sich von den Ideen der

Zen-Philosophie anstecken ließ. Bereits in der ersten Hälfte der 1980er Jahre realisierte er das Projekt Leer-Voll, das Ausdruck seiner Überzeugung

ist, dass das, was am aussagekräftigsten ist, oft

klein und unauffällig ist und durch Kontemplation erreicht werden kann. In Japan schuf er eine

Serie von Werken mit dem Titel Leere Präsenz

(1981), die seine Anwesenheit mit einem Quadrat

aus weißem Papier markieren. Dort, im Steingarten des Kodai-ji-Tempels, schuf er die zur Meditation einladende Installation 5 Ansichten des Kegels: Tag, Nacht (2012). Schließlich brachte Jerzy

von dort Ideogramme mit, die der japanische

Künstler Yasu Suzuka auf seine Bitte hin gemalt

hatte und die seine künstlerischen Interessen

perfekt zusammenfassen: Illusion, Leere, Raum.

Anna Panek-Kusz

I met Jerzy around 2000, when I was a student at the Fine Arts Academy in Poznań, and he was one of my professors. He already had considerable artistic achievements, and he set directions. According to Stefan Wojnecki, he started and promoted the trends of analytical, expansive and elementary photography. The running of the Foto-Medium-Art Gallery or the organisation of four EastWest Conferences “European Exchange” remain a testament to his attitude and determination.

He was charismatic and could infect people with passion. Not only was he active as an artist and curator in Poland and abroad, but he also often gave us, his students entering the world of art, the first opportunity to present our work and participate in artistic events outside the university. I took advantage of it and that was the beginning of our cooperation, e.g. in the organization of the lAbiRynT festival, which in 2010 was moved to Słubice and Frankfurt (Oder). Soon after Jerzy asked me and Michael Kurzwelly to act as co-curators.

This period of collaboration formed me as an artist and curator, it stimulated me in running the OKNO Gallery, photographic workshops, the lAbiRynT Academy or the AKFA Group. I could count on Jerzy’s advice and opinion, always uncompromisingly honest. Why am I writing this in the context of his solo exhibition? Because I would like to show him not only as an artist, but also as a teacher and animator. It is enough to mention, for example, his exhibitions in the form of, as he called them, “artistic dialogues”, meetings and joint activities in the sphere of art or popular science (e.g. with the astrophysicist Marek Abramowicz, the composers Ryszard Klisowski, Rafał Augustyn and Ryszard Osada, the architects Tadeusz Sawa-Borysławski and Witold Szymański, the Polonist Kordian Bakuła), or international workshops “Participation in Community” with artists, poets, and philosophers, held in Jerzy’s country house at Stary Gierałtów.

Jerzy used to say: “Usually, I was an artist when I wanted to express myself briefly, without words”. But he also used words… with a particular fondness coining new ones. His desire to cross boundaries was also noticeable in his visual and theoretical work. He inspired, but he could also confuse those who follow well-trodden paths. He liked abolishing boundaries between disciplines, expanding their dimensions through dimensionlessness, illusions, allusions, deconstructions…

He was fond of artistic recycling. Old CDs provided a base for drawings (The Other Side, 2016), as did the cardboard bindings of student credit work, which he cut into smaller formats. Old Polaroid cassettes and slide frames turned out to be useful as frames for hundreds of works. However, I particularly remember our joint project Hidden Space (2012): three hundred miniature photos, framed in slide frames, were attached to the wooden structure of my house in Urad; the viewer had to look for them by navigating the labyrinth of the house under construction. The miniatures mounted at the time are still in place, like cornerstones, covered with clay plaster. One of the works was not covered and can still be seen today.

The current exhibition, presented as part of the lAbiRynT Festival of New Art almost a year after the death of the artist and my friend, will not give a comprehensive picture of Jerzy. It will not answer all the “why” questions, because he himself was also unable to do so: “Why do I constantly ask myself ‘why’? Why am I constantly breaking up space in order to unify it? (…) Why do I reveal myself only to conceal myself deeper?”

***

I am still uneasy about the uncertainty of both the point and result of my activity. To put it simply, I am concerned with the untranslatability into the visual language of intuitions related to the multiformity of spaces, those impossible ones, and yet–I suppose–finding fulfillment in other dimensions.

Jerzy Olek

In his creative explorations, Jerzy Olek started with photography, but in time he felt he was less and less a photographer and more an artist in the general sense. His exhibitions, always precisely planned for (often untypical) spaces, became elaborate site-specific installations. This was the case, for example, with his exhibition on the walls of Wojnowice castle (Dimensionlessness of Illusion, 2002), inside the wooden construction of a house in Urad (Hidden Space, 2012), in St. Mary’s Church in Frankfurt (Oder) (Extend the Encountered Line by Thought, 2013), but also in more typical places, such as the Arsenal City Museum in Wrocław (Maps of Diversity, 2004) or the Okno Gallery in Słubice (Depth of the Flat, 2003).

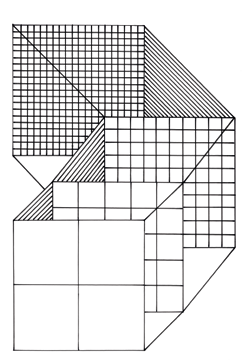

Often, photographs became the material for creating a new form. The artist would cut them up, draw on them, use them in collages or objects, he would extend them into space by building layers– as in pyramids made of many smaller and smaller fragments cut out of successive copies of the same photograph and glued on top of one another (Bending Space, 2007; The Shape of the Ideogram, 2010, Cult of the Edge, 2005). It was not enough for Jerzy to create the illusion of space in the photograph itself; through his objects, he brought photography out of two dimensions into 3D. This is how he called into being Disturbed Space (2011), in which the illusion exists on several levels. A photograph of an illusionistic mural on a new tenement house in Frankfurt (Oder), depicting a historical building that was in its place before the war, was subjected to a process of disruption and spatialisation. One could say that it was a reconstruction of the building in three dimensions.

But three dimensions were not enough; Jerzy felt the allure of higher dimensions. He expressed his insights in this respect by thickening the image. The best example here is The Star (2008). Starting from a stellated 180-hedron made of cardboard (this stage is documented by The Empty Star), the artist covered it with triangles cut out from photographs of the very object, re-photographed the fragments with pasted photographs and repeated the process several times… until The Star itself became an object containing images of images within an image, and perspectives of many other perspectives. But The Full Star (as he called it) also turned out to be only a step towards new objects differently creating spaces within space (Curved Space, 2012).

Jerzy’s interest in space went hand in hand with his passion for revealing the mechanisms of our vision. The structure of the eye, the workings of the mind and the learned conventions of reading the image are responsible for making us so susceptible to visual illusions. And this is another great theme that can be noticed in the artist’s works.

Jerzy first approached the illusiveness of reality through the line. One of his early works juxtaposes a line drawn in pencil and its magnification by means of photography (Magnification of Line, 1982). Later, he supplemented it with an image of the same line from a scanning microscope, thus depriving of reality something that began as a simple line on paper. And the line was important to him in both its physical character and as an idea. It appears in the form of lengths of tape put onto the wall in order to construct projections of figures, as a rule organising the arrangement of exhibitions (e.g. The Depth of the Flat), as strips of photographs stuck on long slats or freehanging (with the image of a cube, with Japanese motifs, inspired by anaglyphs, with a record of meetings with Zbigniew Dłubak, Tadeusz Różewicz or Stanisław Lem). Let’s not forget the line in drawings, for example in the series Possible Figure (2007), where it largely moves towards… the impossible figure. It is also worthwhile to recall an event from lAbiRynT 2013 and St. Mary’s Church in Frankfurt (Oder), when on the anniversary of his 70th birthday Jerzy made an installation entitled Extend the Encountered Line by Thought. It consisted of strips of white kapa board with a variously drawn wavy line. The artist spread these strips on the floor of the Gothic church and illuminated them with tea-lights. The viewers meandered among the lines and contemplated them to the music of the flute. Following his fascination with the line, in 1996 Jerzy created a photographic series Lines of Light, and in 2013, together with a group of artists, he carried out the project Venetian Lines and–at the Venice Biennale–conducted an action entitled Measure the Biennale. In homage to Dumchamp, on the 100th anniversary of his Three Standard Stoppages, visitors were asked to measure the Venetian event using 101cm long pieces of string. Jerzy also analyzed our understanding of the line, asking 59 people–artists, physicists, philologists, composers, mathematicians and poets–to present their own definition. The whole thing was collected in the booklet On Line (2013).

The interest in the properties of the medium led the artist to look at the material carrier of the photographic image. Paper, emulsion, developer and fixer–plus light and time. This is what photography is. This is why it is not surprising to see a series of chemigraphs that involve painting over sentitized paper with photographic chemicals, without using a camera or film (A Series of Coincidences, 2004). This is also the reason behind the triptych Phantom Absorber (2015): Exposing–made up of sheets of undeveloped (and therefore all the time exposed) photographic paper; Developing–made up of sheets of developed paper, and Negative Making–made up of rows of negatives.

Another important aspect of Jerzy Olek’s work is the idea of emptiness. It began with a trip to Japan, where he got infected with the ideas of Zen philosophy. Already in the first half of the 1980s he carried out the project Empty–Full, expressing with it his belief that what is the most revealing is often small and unnoticeable, and it can be found through contemplation. It was in Japan that Jerzy made a series of works Empty Presence (1981), marking his presence with a square of white paper. There, at the Kodai-ji temple stone garden he conceived 5 Views of the Cone: Day, Night (2012) – an installation intended for meditation. From there, Jerzy finally brought ideograms painted at his request by the Japanese artist Yasu Suzuka, perfectly summarizing his artistic interests: illusion, emptiness, space.

Anna Panek-Kusz

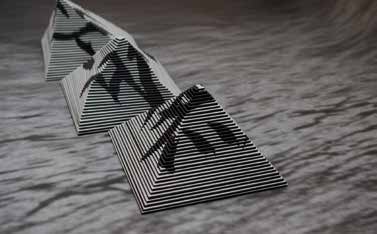

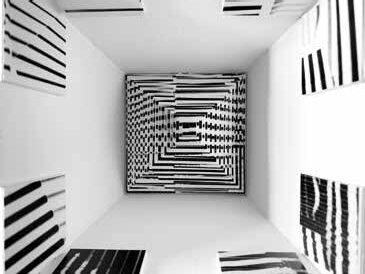

Z serii Kształt ideogramu, fotografia, 90×60 cm, 2010

Aus der Serie Die Form des Ideogrammes, Fotografie, 90×60 cm, 2010

From the series The Shape of The Ideogram, photograph, 90×60 cm, 2010

Z serii Kształt ideogramu, fotografia, 16×16 cm, 2010 (od góry: iluzja, przestrzeń pustka)

Aus der Serie: Die Form des Ideogrammes, Fotografie, 16×16 cm, 2010 (von oben: Illusion, Raum, Leere)

From the series The Shape of The Ideogram, photograph, 16×16 cm, 2010 (from top: illusion, space, emptiness)

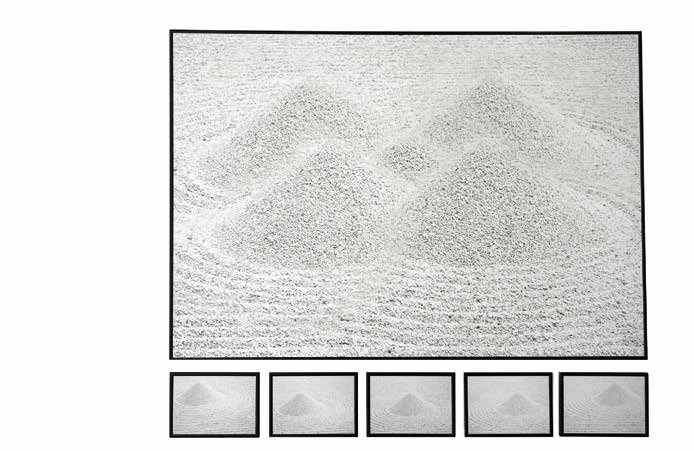

Z serii Pusta obecność, fotografia, 40,5×60,5 cm, 1998

Aus der Serie Leere Präsenz, Fotografie, 40,5×60,5 cm, 1998

From the series Empty Presence, photograph, 40,5×60,5 cm, 1998

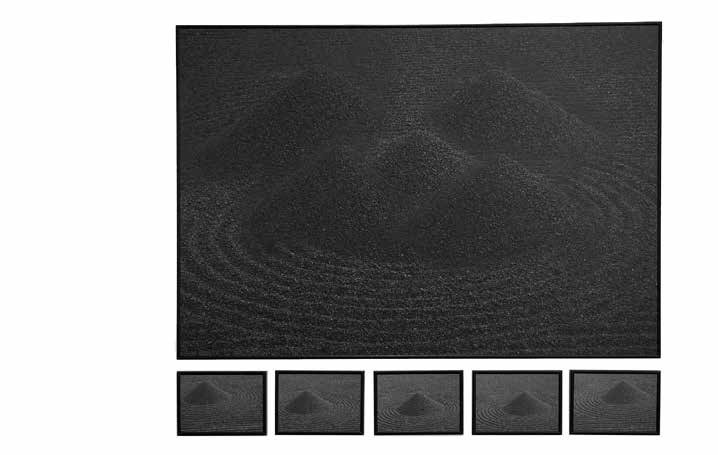

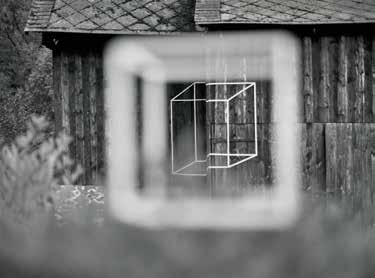

5 spojrzeń na stożek – dzień, noc, instalacja, 2 prace 100×70 cm, 10 prac 18×13 cm, 2012

5 Ansichten des Kegels: Tag, Nacht, Installation, 2 Arbeiten 100×70 cm, 10 Arbeiten 18×13 cm, 2012

5 Views of the Cone: Day, Night, installation, 2 works 100×70 cm, 10 works 18×13 cm, 2012

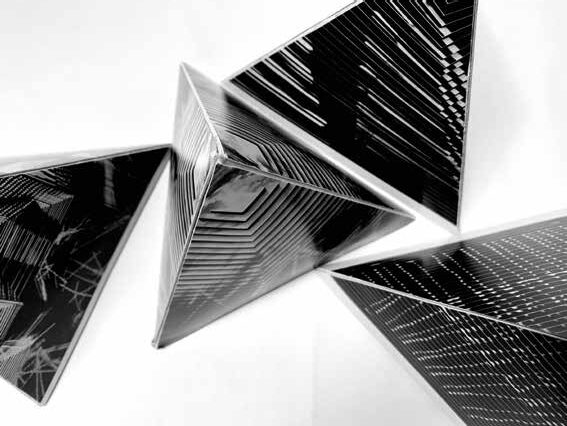

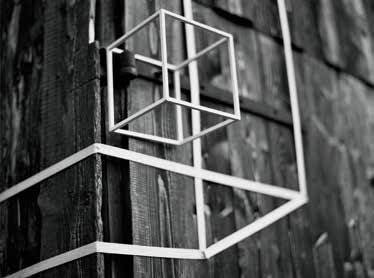

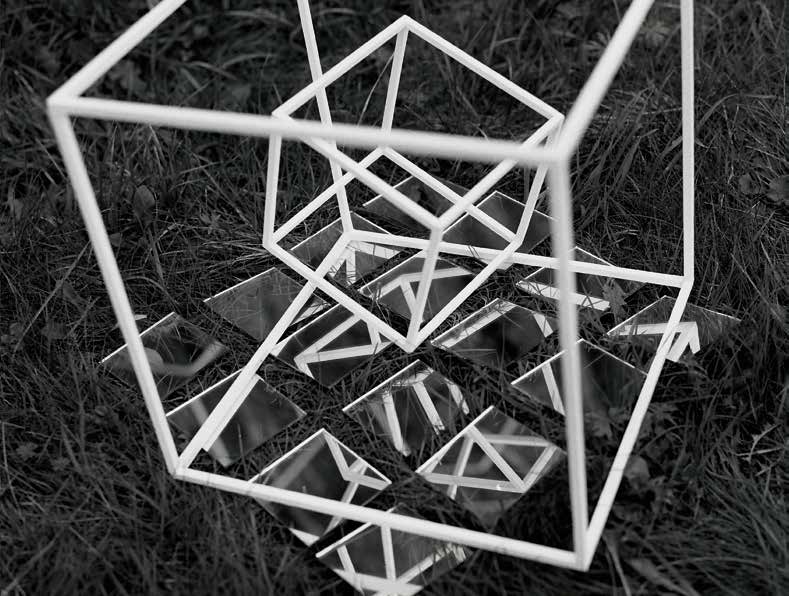

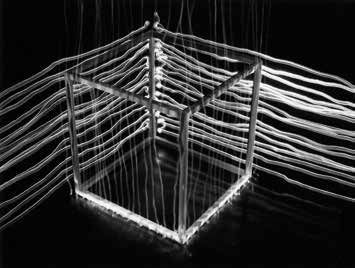

Z serii Zaginanie przestrzeni, obiekty: 16x16x16 cm, 2007, fot. Anna Panek-Kusz

Aus der Serie Die Verbiegung des Raumes, Objekte, 16x16x16 cm, 2007, Foto Anna Panek-Kusz

From the series Bending Space, objects, 16x16x16 cm, 2007, photo: Anna Panek-Kusz

Z serii Zaginanie przestrzeni, obiekty, 16x16x13 cm, 2007

Aus der Serie Die Verbiegung des Raumes, Objekte, 16x16x13 cm, 2007

From the series Bending Space, objects, 16x16x13 cm, 2007

Bez tytułu, obiekty, 16x16x13 cm

Ohne Titel, Objekte, 16x16x13 cm

Untitled, objects, 16x16x13 cm

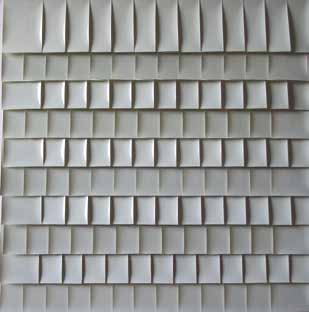

Pochłaniacz fantomów: Luxus Bromoza LS 1 – naświetlanie, obiekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Phantomfänger: Luxus-Bromoza LS 1 – Belichtung, Objekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Phantom Absorber Luxus Bromoza LS 1 – Exposing, objekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Pochłaniacz fantomów: Luxus Bromoza LS 1 – wywoływanie, obiekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Phantomfänger: Luxus-Bromoza LS 1 – Entwicklung, Objekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Phantom Absorber: Luxus Bromoza LS 1–Developing, objekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Pochłaniacz fantomów: negatywowanie, obiekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Phantomfänger: Negativierung, Objekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Phantom Absorber: Negative Making, objekt, 50×50 cm, 2015

Kolczatka pusta, fotografia, 73×73 cm, 2008

Leere Stachelkugel, Fotografie, 73×73 cm, 2008

The Empty Star, photograph, 73×73 cm, 2008

Kolczatka pełna, fotografia, 73×73 cm, 2008

Volle Stachelkugel, Fotografie, 73×73 cm, 2008

The Full Star, photograph, 73×73 cm, 2008

Z serii Zagięta przestrzeń, obiekty, 50×50 cm, 2012, fot. M. Koch

Aus der Serie Der Verborgene Raum, Objekte, 50×50 cm, 2012, Foto: M. Koch

From the series Curved Space, objects, 50×50 cm, 2012, photo: M. Koch

Przestrzeń zakłócona, instalacja, 2010

Der gestörte Raum, Installation, 2010

Disturbed Space, installation, 2010

Przenikanie, fotografia, 90×75 cm, 1996

Durchdringung, Fotografie, 90×75 cm, 1996

Penetration, photograph, 90×75 cm, 1996

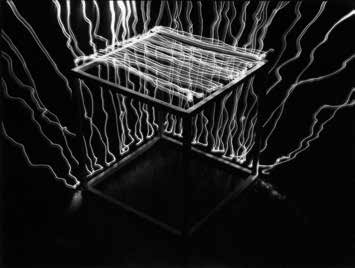

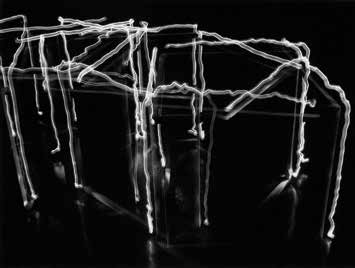

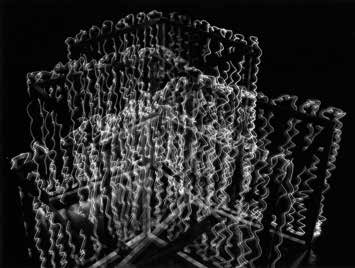

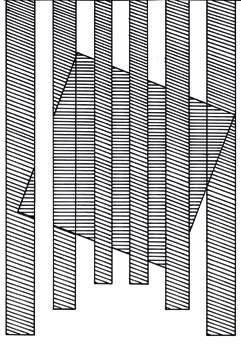

Z serii Linie światła, fotografia, 70×50 cm, 1996

Aus der Serie Lichtlinien, Fotografie, 70×50 cm, 1996

From the series Lines of Light, photograph, 70×50 cm, 1996

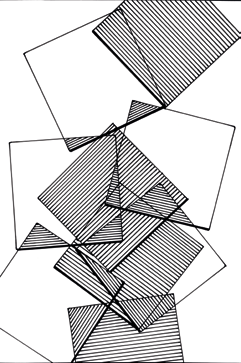

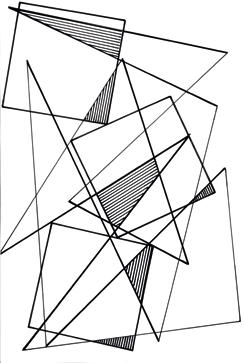

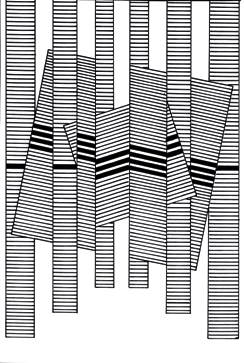

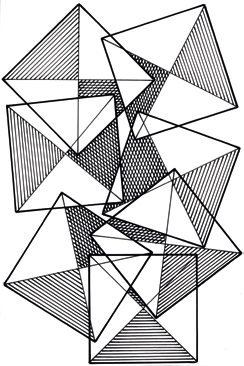

Z serii Figura możliwa, rysunek, 9,3×14 cm, 2007

Aus der Serie Mögliche Figur, Zeichnung, 9,3×14 cm, 2007

From the series Possible Figure, drawing, 9,3×14 cm, 2007

Powiększenie linii, rysunek ołówkiem, fotografia, 52×25 cm, 1982

Linienvergrößerung, Bleistiftzeichnung, Fotografie, 52×25 cm, 1982

Magnification of Line, pencil drawing, photograph, 52×25 cm, 1982